My daughter, who publishes Gardenerd.com resides in Santa Monica CA, and recently with helicopters overhead signalling the unrest of massive protests against the indefensible injustice that caused the death of George Floyd, she felt strongly complicit of corporate guilt in the ongoing existence of Racism. I so love this woman; this is her self-reflection;

I’m not very articulate when it comes to expressing shame, but that’s what I feel when I think of how long it’s taken to understand how my whiteness has made my life easier and safer than any Black or Brown person’s life. For a long time I, like many, thought that doing well in life was a matter of making good decisions, choosing the right role models, and showing up with integrity when the occasion calls. And that the fate of others less fortunate was a direct result of choosing to do the opposite.

But that’s a misconception. That is one of my many unexamined assumptions about black, indigenous, and people of color. The truth is that “doing well” in life has everything to do with equality or the lack thereof. The sooner we admit there is racism, inequality, and systemic suppression of some but not others in our daily existence, the sooner we can start to address the real reasons why Black and Brown people aren’t doing well in this country.

Sure, my life was challenging as a kid. I was “on the outside looking in” at my dreams and goals, and was bullied and ostracized for being nerdy and scrawny. I had multiple experiences of #MeToo as a child that made me afraid of men in general. But I could always walk into a store without the owners eyeing me as a potential thief just because of the color of my skin. Being white spares me from scrutiny, suspicion, and disrespect. Statistical data supports this argument (I wouldn’t be a Gardenerd if I didn’t present the research).

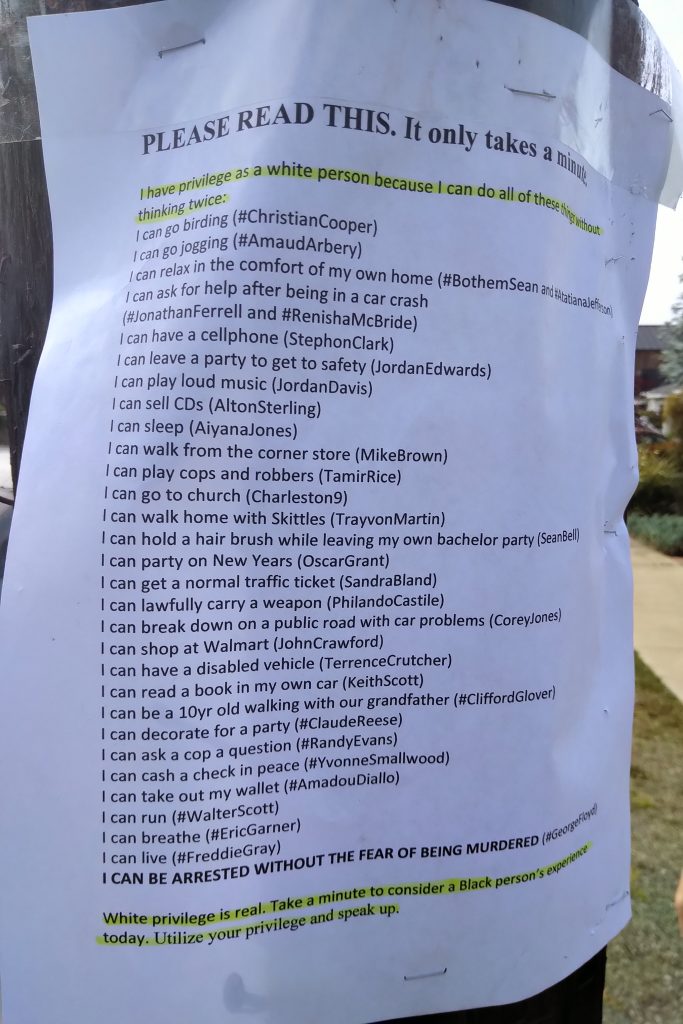

Even as a woman, I can apply for a home loan, something that was denied for decades (and is still in some places) to black people. Mortgage rates are higher for them, business loans are denied more often for them. The very foundation of our economy is denied to a portion of society because of race. Covid-19 is disproportionately affecting black and brown people, not only because they hold jobs in “essential” services (and are paid less than whites holding the same position), but because they don’t have access to proper health care, and they are treated differently than whites by providers. The list goes on with disparities between how blacks are treated vs. whites at every turn: arrests, criminal sentencing, job hiring. I know I couldn’t succeed in the face of that opposition. And that’s not even the overt racism embedded in our country’s history, that we still see all over. No wonder people are raging over yet another death of an unarmed black man.

Systemic oppression is centuries old, and the task to unravel our preconceived notions, our assumptions, and yes, inherent racism is a daunting task. To say that racism is dead or over is ignorant. To say that we–whomever we are–don’t play a part is irresponsible. To be silent is unconscionable.

I am taking steps to address my inherent racism. This article is step 1. My step 2 is to take an anti-racism course by Layla Saad. I hope you will join me in evaluating your own inherent racism, peeling back the layers of unexamined assumptions about black, indigenous, and people of color.

If you are not ready to peel back the layers, at least acknowledge that racism exists and is at play every day. That’s a good starting point.

[Christy Wilhelmi, The Gardenerd] Gardenerd.com

I post this because I am generally aware of my own blindness in every-day life to the difficulties of being “Other” than a white majority. But I am keenly aware of how my whiteness has made my life easier. I strongly felt this injustice when I was growing to adulthood, because it was flagrant and all around me. However, I had a sense that I could only control my own behavior in this regard; that the larger battle to change the culture was not my fight. But I became a Catholic specifically because this was the Church of all peoples, of all nations, of all races from its early beginning, professing, over two thousand years now, that all lives are sacred, known and held by God as brothers and sisters of His only Son, equally welcome to sharing in the Kingdom of God. I try to live that belief, but as most of my activities are involved within the Church, indeed my local Parish, I rarely run into overt racism. I have spent the last 45 years of my life, with my wife Jo, bringing people of all shapes, sizes, colors and races into the Church as a catechist, doing my prayerful best to treat all with the love God has given to me. I have to say though, that I feel the uneasiness of “otherness” when I find myself in the parts of ‘anytown’ where there are few people who look like me and I don’t know any of them. And I would never be found in a massive protest at 80 years old with a seemingly small bladder. I really don’t trust mobs, and I think justifiably for the most part.

One resent experience caused me to ponder this sensing of otherness and the unease it creates: My next door neighbor in my previous home was a very dark-skinned Nigerian and his wife and three likewise very black young adults. We hit it off quickly as he worked in aerospace, and like me, was an engineer. The kids made friends more slowly, and one day chatting in the front yards the youngest was ignoring my presence, and dad cajoled him to be respectful and say hello. After that we talked often. One evening well after dark I was in my driveway and a car pulled up in the neighbors driveway, someone got out looked over at me, said nothing but stood for a while. Dressed in dark pants, a black hoody pulled over his head, over a baseball cap, I had no idea who IT was. And that’s my point: I instantly lost any sense that IT was a person. All I could see was a black form. Then he spoke and I knew he was Akinshola, the youngest son. It stuck me how I can recognize a white person in the dark quite easily, but had only a vague sense that the form in the other driveway was human. I felt no connection. I wonder how common this is, and how impactful it is in race relations. But I think if I were black I would never dress to hide my features from those around me. One of the most profoundly distressing books I ever read was “Black Like Me” written by white journalist John Howard Griffin, who took a drug to turn his skin dark and frizzed his hair to look Negro (means Black ya know, but out of fashion) and traveled the southern US in the late 50s. He suffered greatly at the hands of both the peoples and the authorities. He chronicled the institutionalized injustice he encountered and his experience of bias in every aspect of simply trying to live. Worth reading to grasp the debilitating difference in “Freedom” encountered by just being Black. It seems we still have along way to go overcome racism in the US, and the rest of the world is hardly ahead of us.

Frank

Frank Wilhelmi - Retired/consultant electronic engineer researches and reports practical strategies for optimizing health and fitness into advanced age. “I have a passion for living life to the fullest, and helping others to do the same.” A rapidly growing body of knowledge now enables us to extend our health and fitness decades beyond popular expectations.